The power of the testing effect has wide currency and is identified by Dunlosky et al as the most effective method that pupils can use in order to build long term memory. This sounds wonderful, but there’s a problem. Does telling a pupil to self-test actually lead to them self-testing? And if they do, are they actually doing it in the right way? To become good at this is actually quite difficult so it needs to be modelled in the classroom first. What follows is a process I used this term with my National 5 history class (the Scottish equivalent to GCSE), so I hope it provides a practical case study that others find useful.

Step 1: calibrating the knowledge base

The most difficult thing for pupils to become familiar with at the start of this particular history course is the standard of the knowledge they need to learn (and be able to recall). The content we covered is a unit called ‘Migration and Empire’ that addresses which groups came to Scotland, as well as where Scots emigrated to, in the period from c.1830 to 1939. The first section looks at Irish immigration after the famine of the 1840s, so pupils need to know technical terms like ‘potato blight’, statistical information (the population of Ireland decreased from 8 million to 5 million), facts about where Irish people settled in Scotland (e.g. areas of Glasgow like the Saltmarket) and concepts like ‘strike-breaking’. They need to be able to recall some fairly precise information and the standard is higher than they are used to.

Having taught the content, the first factual test consisted of 30 questions divided into 6 sections, half of which were multiple choice. The class were given some instruction in metacognition and advised on how to self-test, but this was little more than an introduction. Until they’ve actually tried putting theory into practice, it won’t mean much. The first test was therefore tough and the average mark was just 16.2 out of 30. Pupils marked it immediately (Dylan Wiliam’s advice is that the best person to mark a test is the one who just sat it) and I took in the scripts to do some (swift) number crunching to give whole class feedback. The final section of the test on Irish occupations scored the lowest and needed some reteaching to correct misconceptions.

Step 2: applying metacognition

The second section of the course looks at other immigration groups to Scotland – Lithuanians, Jews and Italians. This time we could prepare for the test using a scaffold of types of knowledge, which we identified by looking back at the last test (the recipients were definitely doing more work than the donor at this stage). They had to go over previous questions and answers to think about knowledge types and we set up this framework:

- Key terms and concepts

- Events and processes

- Key individuals and groups

- Statistics/facts

This allowed pupils to categorise information using knowledge organisers I made, but they populated. The second test used the same structure as the first, and the average mark rose to 22.6 out of 30. Number crunching afterwards showed no particular section was weak, so no reteaching was needed.

Step 3: teaching to self-test

The third part of the course is on reasons why Scots emigrated and has some tricky knowledge on the Highland Clearances, poverty in the Lowlands, and incentives like government-sponsored emigration schemes. The knowledge for this is the hardest to break down and organise logically.

This time, once we’d covered the content we did a lesson on how to construct a test. Homework beforehand was for each pupil to come up with 10 questions and answers on the material we’d covered. In class, they worked in pairs on a combined list of 10 questions based on comparing their efforts. They then doubled up with another pair and refined this further. We then came together as a whole class and, with a scribe typing things up on a computer and projected on the screen, we took the best questions and answers and wrote a 30 question test.

This exercise allowed us to stop and think about what knowledge we need to recall, and how best to frame a question that would test our ability to recall that. This led to lively discussion about the wording of specific questions, as the main problem pupils have with history self-testing is they ask open questions that are more like essay titles. For example, instead of asking ‘when was the depression in the fishing industry?’ (answer: 1884-1894) they ask ‘why was there a depression in the fishing industry?’ It’s a valid question, but it’s for full written practice, not a low stakes test. When we had written up 30 questions, we worked on turning half of them into multiple choice (which is trickier than they realise – they need 3 credible wrong answers for every question). I then took the document we drafted and edited/formatted it, with only one question needing a rewrite by me before pupils took the test in the next lesson.

So what was the outcome? The class average was 27.2 out of 30 (so over 90%), and the pupil with the lowest score in round one achieved 100%. You may well say ‘of course they did so well, they knew the questions in advance.’ Yes. That’s the whole point. The assessment here wasn’t so much about answering factual questions but how to make them. In giving feedback I focused on the fact that some pupils had contributed more questions than others to the test, so some still have to practise how to make a good test. However, we’ll keep working on this so it becomes easy – and, hopefully, transferable to other subjects.

Step 4: the forgetting curve and self-regulation

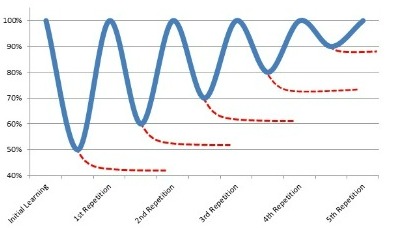

I observed a lesson once where a Year 11 pupil couldn’t remember a piece of information from the year before, and when the teacher followed this up it turned out they couldn’t remember even having learned the entire topic. This shows the half-life of knowledge, so the forgetting curve needs to be defeated with spaced practice.

So what I did with each of these tests was turn them into a Kahoot. We allowed enough time (at least one week) after each test before doing it again as a Kahoot, and this showed that some information types were harder to retain than others (no prize for guessing the chief culprit – statistics). Over time we’ll build up a bank of these which pupils can use for self-testing and will return to them periodically in lessons. When we’re midway through the Transatlantic Slave Trade next term we’ll still spend 10 minutes doing an old Kahoot on Irish immigration to Scotland. This means I can have a weekly test with much less effort, so my jealousy of maths teachers who seem to test with ease might finally subside…

Making effective use of the forgetting curve works wonders for long term memory, but it also shows pupils how easy it is to self-test. I estimate that we’ll have about 15 such tests by the end of the course which means they will have at least 450 pieces of precise knowledge on entering the exam room, so the ammunition will be there to provide evidence in all essay questions.

The crucial final ingredient is taking the pressure out of the testing in this process. The last test was both the least stressful and the most successful. The message here is that to get pupils to want to self-regulate by testing themselves you need to reduce the stakes first. Emphasise that a test isn’t about data collection (though I obviously did that in this example, as a diagnostic), or reporting. The crucial message is that tests are about practice. The first mark you get is far less important than the last mark you get. The more you self-test, the better your recall, and the more you build confidence. Once they experience this process so it feels real rather than abstract, they will be far more likely to do what we want them to do: take up the challenge of learning for themselves.

2 thoughts on “Harnessing the power of the testing effect”